|

Weebly's new for me, and it honestly hasn't been the most friendly program for blogging. (Of course, it is free.) Ideally, I'd like to rearrange the entries here so they run in forward order from Day 1 to Day 18, but that doesn't seem possible. Doesn't even seem to be possible to create an easily clickable calendar of the festival.

So, here's what you can do if you're trying to do research. Go to Categories on the right: select the name of the artist you want to know more about, a location, or a theme. If you're researching the whole of this year's FCP, select the day - Day 01 Yangon, etc. Entries will be displayed in reverse chronological order. You can also just click on Artist Interviews above to get a sense of how the artists felt about the event in retrospect. Be warned: it's

0 Comments

I've been dragging my feet on this final post, which I've saved for last because it commemorates the most vital elements of the Flying Circus Project: the administrators, technicians and volunteers who worked behind the scenes to keep things going. It's a non-comprehensive list, and it doesn't have everyone's names. Will fill them in via crowdsourcing. Lemme know via comments if I've mislabelled anyone!

Just wanted to show this off. These sarong-like garments are super-cheap and loads of fun to wear. The only problems are that there are no pockets (I hung my camera from a buttonhole in my shirt) and it's tricky to tie (Nge Lay had to help me a bunch of times.) True story: I wore this to the National Museum in Yangon, and an American lady, surveying the exhibits, turned me and said, "You must be so proud."

Well, I'm not Burmese (though I'm told I could pass off as Shan), but I am bloody proud of my Southeast Asianness. Fully intend to teach in this outfit in Singapore, too. Sorry it's been so late since the last upload of Alter U participants! Here are a few I managed to get in the last couple of days.

Kaffe and Tellervo, improvising a song in the bus at Mandalay Airport. A ticket tag from the Swedawmaw Pagoda (or is it the Shwedagon?) discovered on Tellervo's camera strap while on Pulau Semakau, Singapore. And perhaps most precious of all, the random chatter between us on bus rides between the BFI and the hotel in Yangon. I'd already reviewed the final installment of the Wathann Film Festival, which was Oakkar's "The Last Drop of Rain" and Maung Wanna's "Wearing Velvet Slippers, Holding a Golden Umbrella". And it was 7pm and I was hungry and tired, so I got the hell out of TheatreWorks and headed home. What I didn't expect was that it would feel so hard to leave. I was saying goodbye to as many folks as was polite, slowly cutting off the physical thread that bound me to this 18-day event.

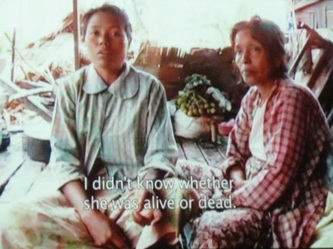

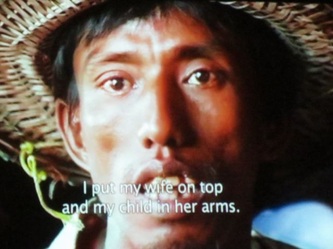

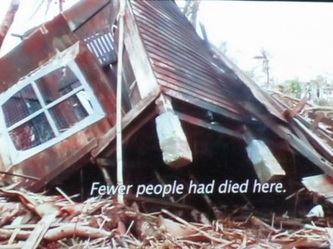

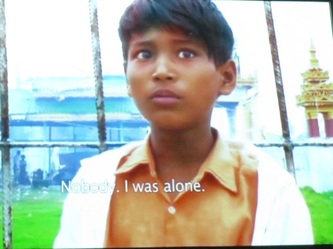

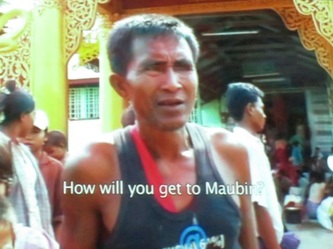

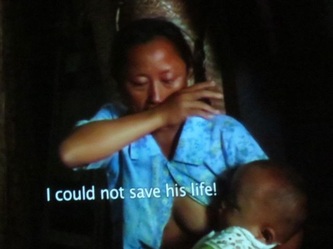

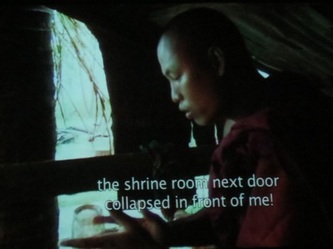

Being a Singaporean archivist of FCP when you're in Singapore is weird: you're no longer staying with the artists so you're cut off from some of the more informal aspects of their communion, which is one of the really wonderful bits of the whole experience. And you're no longer on holiday: you go back home and there's a million and one things to be taken care of, and there's no novelty to your surroundings to inspire you, so you're bloody tired all the time. But you also know you should thank your lucky stars for being able to see TT and Keng Sen almost anytime, being only a stone's throw from Myanmar and all the other wonderful Southeast Asian nations whose people are doing great things in the early 21st century. You get to stay on. For the next few days, I'll be adding some residual documentation which I didn't upload earlier. After that, if anyone could teach me how to reverse the chronology of this blog - so you can read it from beginning to end, not vice versa - that'd be amazing. Cheerio for now, Your friendly blogger, Yi-Sheng I was actually furious at the thought of having to sit around waiting for this film to start. I'd planned to leave by 2pm and finally get some rest. Now, because of some stupid 90-minute documentary added to the Wathann Film Festival, I had to stay back till 7. I was tired and sick (and Singaporeans don't get per diems when we get back to Singapore, btw.) So I crawled into the screening room thoroughly determined to hate the movie. But it sucks you in, you know. All this trauma, all these extremely specific tales drawn from the survivors: farmers, craftsmen, healers, monks, fathers, mothers, orphaned children. These are their testimonies: dead bodies floating like thousands of ducks, villages drunk on liquor for days because there's no drinkable water left, a woman who had to strip naked in the flood because everyone sinking was clutching to her clothing and pulling her under, a child pulled along in a current, caught by the branches of a tree, waking in the morning to realise he'd been sleeping on a dead pig. Although the film's officially directed by The Maw Naing and Pe Saung Same, it actually involved a huge crew of film students, including Thu Thu and Thaiddhi. They managed to reach the disaster-stricken area 7 days after the cyclone and went on shooting for three months, spending 7-10 days in the area, going back to Yangon for 1 or 2 days, over and over again.

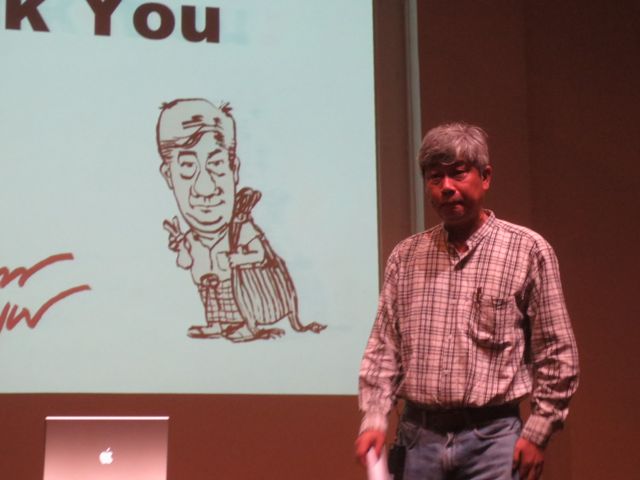

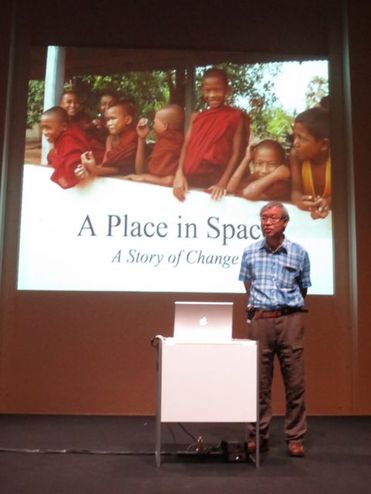

The media, it seemed, showed plenty of dead bodies. They restrained themselves: what concerned them wasn't so much the dead but the living, who were trying to rebuild, trying to find the bodies of their loved ones, trying to survive on the government's aid rations of 1 cup of rice per person every 12 days. Plenty else to blame the government for: they predicted the cyclone to be 70-80 mph (real strength was 120mph) and just said "take care" - no instructions. Thu Thu started out as a camerawoman, but her hands kept shaking as she heard the stories - she ended up doing production management instead. Two directors, two cameras, two sound people at all times, 70-80 hours of footage. Interviews carried out with extreme sensitivity: coming without cameras into the community first, building their trust, ensuring their sense of safety at all time, listening to their stories and thus giving some closure to their pain. They didn't have money to give, Thu Thu said, so this was the best gift they could offer. This was risky business, remember - it was back in 2008, just after the Saffron Revolution. The government had declared that it would arrest anyone shooting film there. Once, they encountered officials and just lied and claimed they were from some NGO group. The officials were confused enough to let them go on shooting right out in the street. The crew kept diaries of their reflections, thus creating a narrative voice that was more poetic than journalistic: quoting the five forms of great disasters in Buddhist scriptures. Does the water remember? Or the trees? Because of censorship they couldn't screen this in Myanmar for years: they did post-production in Hamburg, and released it at an international film festival in 2009. But then, two crew members got arrested so they decided to withdraw the film, replace all the names in the credits with pseudonyms. The second Wathann Film Festival in September 2012 was the first time the film was shown back home. Over 500 people attended the premiere, and the original names of creators were reinstated in the credits. It would've been cowardice, Thu Thu said, for them to hide themselves, when the survivors ran just as great a risk by putting their faces on screen, sharing the truth to the world. Since San got banned, we actually got a break between APK and the filmfest, which the tech guys spent doing setup. A much-needed pause for my concentration, and a period for a few more audience members to trickle in from outside. We slumped ourselves on the beanbags and let the Festival Directors do the talking. Thu Thu: We always have a problem to shoot in the country. Whenever we shoot in the street or someone’s house, we need the permission to shoot. And even after the films were shot, there was the problem of getting them past the censors. Much too hairy a process, everyone thought, so they passed their films from friend to friend through underground networks, only getting glory at international film festivals. Not an ideal situation. They decided to go for broke in 2011 and hold the first Wathann Film Festival in a Buddhist centre. Fortunately, the censors were pretty confused and didn't take action - after applying two months in advance as instructed, the organisers only got their approval letter an hour before their closing ceremony! Ah well, legal is legal. No problems this year, 'cos the censorship board's been dissolved. Audiences grew from 500 to 4,000. (You see, Singapore? So much could happen if you only got rid of our censors!) The actual lineup of movies overlapped almost completely with what we saw in Mandalay: stuff I reviewed here, here and here. The first and the last films were different, though, so I couldn't rush home and finally get my beauty rest.  Social Game, dir Seng Mai Yeah. As I said, I was tired, and I was cranky, and I couldn't see the flippin' point of this movie. It's filmed among in a Kachin minority settlement, which is cool, but the content makes very little sense. Two threads intercutting one another: Q&As with a class of schoolchildren, where they answer, "What is the most important thing for your country?" They give the textbook answers: money, education, politics, health, each of which open up a new section of the film. Unfortunately the action is utterly prosaic and bears very little relation to the supposed headers. Ten minutes of my life I'll never get back.  Nargis - where time stopped breathing, dir The Maw Naing and Pe Maung San Now, this documentary deserves a post of its own... Yes, cartoonist APK used the same slides as before, but his presentation was markedly different. For starters, he chose to speak in English rather than Burmese. And for the main course, he digressed into all these further revelations. Didja know that his name, "Aw Pi Kyeh", just means "loudspeaker" in Burmese? APK: In my country we have two names: real name and pen name. Because in Myanmar, the names are very similar to each other, because most of the names are two or three words. Plus, he started out as an engineer - but how did he end up becoming a cartoonist? APK: After the 1988 uprising, I was one of the leaders and I was forced to retire. Also some of my engineering friends were also forced to retire. They moved to Singapore, Australia and other countries and they work as engineers. But I decided to be a full-time cartoonist. Because I believe in cartoons when I was young. Cartoons are very powerful and very effective. It doesn't make him that much money, though - he relies on the computer skills he learned to rake in cash as a techno-savvy graphic designer. Of course, now it's about his passion for the craft. He spoke of all the metaphors of cartooning: how he's a loudspeaker to amplify voices. Others say cartoons are a mirror; the first Burmese cartoonist, working in the 1950s, called it an X-ray - examining issues with some penetration. And of course, the good old football metaphors - he wants to be the referee, showing the government red and yellow cards, but it's the government that issues him warnings instead. Even banned him for a year from cartooning, just because he gave a bag of rice to the protesters of 2007. Now, he's bent on public education - one of his handbooks is about disaster readiness, explaining what to do if another Cyclone Nargis hits. He never does what the NGOs want him to do exactly: he tweaks it to touch the public heart, to stay in the public brain, and above all, to be comprehensible. APK: In 2000 I visited Singapore, I went to Popular Bookshop, and I picked up a textbook. And the textbook was history. But the printed name wasn’t history. It was “Understanding Our Past”. That is very good. If you ask children what is history, they will say, it is not geography. But this is history. Understanding our past. This is easy to understand. Nice to know we're doing something right, sir.

Actually, that wasn't so bad. I was grumping during the actual presentation - all the same slides as before, barely any new info - but the talkback was super-active, revealing plenty I didn't know. For instance, his monastery school program is a semi-underground operation, constantly wary of the government. Ko Tar: We have to do it quietly. Because the monks were involved in 2007 protests, and the government has fear of this old society. If you are doing things with the monks, you have to be careful. They are concerned although it is apolitical... *apparently* apolitical. KS asked about the future: how the monastery schools would deal with the coming of democracy. Ko Tar: The last 50 years, what we are concerned with is about the military dictatorship. Now we have to work with market capitalism. Oddly enough, he says he isn't very Buddhist himself. Ko Tar: When people ask me what is my religion, I say my religion is compassion. Actually our teacher trainers are mostly Christians. The work with the monks is about access to the community, giving poor kids skills of literacy and good citizenship and pride in their culture before they turn 12 and their parents send them to the fields to work.

And surprise, surprise - remember how KS said he also runs a high school for middle-class kids? I'd assumed this was just his regular day job, but it's actually part of his activism. Public schools are trash and private schools are the exclusive domain of the super-rich. It's only these schools that'll give an average professional's kid the chance to learn English and go to university. Parallel structures. It's not about equal education - you need the mammoth mechanisms of a functioning government for that. Right now, it's about helping kids, whatever class they are, and giving them what they need to move forward. |

AuthorMy name's Ng Yi-Sheng, I'm a writer from Singapore, and I've been a Creative-in-Residence with TheatreWorks since 2006. I've served as blogger-documenter for two previous Flying Circus Projects: Singapore/Vietnam in 2007 and Singapore/Cambodia in 2009/2010. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed